By Kristina Smith

Jane Marshall, a seasoned travel writer with a 17-year career, has spent her time exploring the world in search of remote and elevated destinations. Her wanderings have led her to a striking discovery.

On three different continents, spread across great distances of sea and land, she has stumbled upon secret valleys referred to as “Happy Valley” by the locals.

Intrigued by the concept of happiness in these regions, Jane has embarked on a quest to uncover their secrets and glean wisdom from the Indigenous communities who inhabit them.

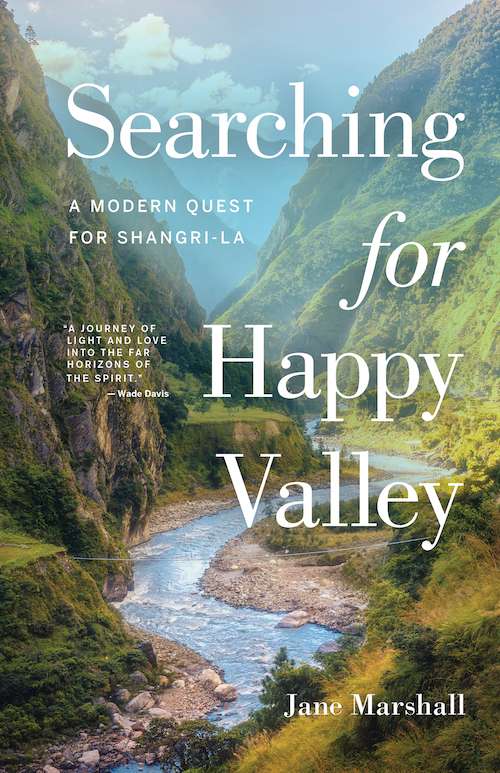

In her new book, Searching for Happy Valley: A Modern Quest for Shangri-La (Rocky Mountain Books; April 2023), Jane discovers that the Happy Valleys she encounters share several distinctive traits: they are geographically isolated, surrounded by towering mountains, and home to rare and endangered flora and fauna.

These valleys exist outside of protected areas, granting them autonomy but also leaving them vulnerable. Their Indigenous inhabitants name the land after body parts, both human and divine, and women hold a position of power within the community. Within these valleys, a harmonious relationship between humans and nature has been achieved.

Traversing rough terrain and sleeping in local homes, caves, and ridges, Marshall journeys to the heart of these Happy Valleys to understand the profound peace she feels within them.

From a goat herder’s dwelling in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco to participating in a Sundance ceremony with the Blackfoot/Soki-tapi people of Alberta, and finally embarking on a perilous pilgrimage in Nepal to the center of a sacred land where a renowned yogi has hidden treasures, Marshall takes readers on an epic adventure in search of Shangri-La and the wisdom that can save both the planet and our own hearts.

In a world beset by environmental crises, illness, and unprecedented mental anxiety, Marshall’s book provides a much-needed alternative. She fully immerses herself in the land and forms deep connections with its inhabitants, learning sustainable ways of living that Indigenous populations have refined over millennia.

An extraordinary read that brought me to tears more than once.

The Happy Valleys, as Described by Author Jane Marshall

Ait Bougemez, Morocco

This African happy valley is nestled in the very centre of Morocco’s Atlas Mountains. It is the traditional home of Indigenous Amazigh/Berber people who strive to preserve their unique language and culture.

Entering Ait Bougemez with my young children and husband with our Indigenous guide Ahmad was incredibly special. We were able to be absorbed into the people’s daily lives at the market and on their farmland. The highlight was a trip to Ahmad’s family goat hut above the main valley.

Here, as in the other happy valleys, the land had human names and attributes (head, shoulder, mouth). I was moved by the deep, multigenerational connection to the farmland and animals and to the semi-nomadic lifestyle of Ahmad’s cousin, Said, who cared for many goats.

Happy Valley, Alberta, Canada

I felt a chasmic disconnect to the Indigenous cultures of my own province. So I worked hard, and carefully, to find ways to form relationships and immerse myself.

First, I learned about the area’s ranching culture and my own connections to the land there (mainly my Grandpa’s wish to settle there). Then, I dug deeper and connected with Conrad Little Leaf, an interpreter at Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, then attended a Sundance ceremony and sweat lodge on the Piikani Reserve.

Learning the Indigenous history of the land that was ironically called Happy Valley by ranchers because people were squabbling over land rights, I found out what truly made the valley happy.

The ancient nomadic ways of the Blackfoot/Soki Tapi people, the carbon capture abilities of the grasslands, and the history of the buffalo. When I decolonized myself, happy valley let me in.

Kyimolung Beyul, Nepal

After more than a decade of research and trips, I made my way to the centre of this sacred landscape by following a guidebook created by an ancient Tibetan Buddhist master. It promised to open the gates to a sacred land where one can find treasure and lasting happiness.

Travelling with a Tibetan Buddhist nun, guide, and two porters, we were able to enter and find key locations from the guidebook. Ani Pema and I ascended a high ridge and found a rock formation called Senge Dongpa Chen, home to a wrathful female deity and a location that is said to hold hidden Buddhist texts.

We also met the area’s only nomad who shared his knowledge and showed us his simple lifestyle, and made the dangerous ascent to the holy mountain called Tashi Palsang. Hidden behind a massive, dying glacier and around fierce 800m plus cliffs, we found Tashi Palsang, the heart and centre of the valley of happiness that holds the greatest number of hidden treasures.

We realized that the lesson was not only in attaining our goal of finding the mountain, but in being vulnerable in a remote and dangerous wilderness, and being at peace with the land and with ourselves.

[Book Excerpt] Circling Back to Ahbak, January 4

Another hiking day. Lunchtime. We sit at a picnic spot at the edge of a farm plot at Ait Wanougdal village, where the valley has no choice but to give way to the rising hills. The poplar bark gleams silver, and the sky is painted potent blue. Ahmad has brought a simple meal of boiled potatoes (which we sprinkle salt on), tomatoes, handmade bread, olives, tinned mackerel, and dates and oranges for dessert.

‘Our walk to this spot has me struck with wonder. There is electricity in the homes, and there is education and accessible health care (though the Amazigh people had to fight for these rights) – yet people are living traditionally. They are connected to their ancestors through their very homes, which have been passed down for generations and modified with love and need with each new family. What would it be like to live this way all the time? To belong to the land? I think of how the majority of Canadians like me are descended from European immigrants, and how we lost our ancestral connections to the land. Ahmad’s roots are obvious and deep. I wonder where my own are. Are they in my home city of Edmonton, Alberta? My family has lived there for less than 40 years. Are they in Calgary, where I was born? Perhaps in southern Alberta, where my grandma was raised as a farm girl on the prairies? There is a strange gap inside me, a gap that leaves me floating and untethered. I seek out these cultures and the places that grew them so I can see, name and understand this gap inside, and better understand my lack of belonging.

Butterflies dance among thick blades of grass as we munch on our food. Ahmad hears something in the grass, then spots a puppy. He coaxes it over with the promise of a treat. Julie has always loved dogs, even though she was once bitten quite badly by one. She was more upset that the dog didn’t like her than she was of the tooth marks it left on her eyebrow and chin. This little pup is young, with soft hair and slithery skin it still needs to grow into. Julie takes it into her arms and bathes it with love.

Ahmad explains (out of earshot of Julie) that rabies is a problem here, and that each summer there’s a campaign to shoot infected dogs. He looks at the pup and says that its mother is gone and that it won’t survive. When it’s time to move on, Julie refuses. She holds the dog, and in her young mind realizes for herself that it’s not going to make it on its own. “How can we just leave it here?” she cries. I know Mike, Ben and I are thinking the exact same thing. Yet we extricate the puppy from her grasp. Julie sobs into her dad’s chest, and he holds her until the internal earthquake has moved through.

Life and death are apparent in this Shangri-La. Though humans wish for utopia and long life in a “perfect” place, the truth is that life is naked and raw, and death is real and unhidden. Perhaps the tradeoff for such vivid, visceral landscapes and experiences is that death is included in it all. We are granted the entire picture, and we must become strong enough to endure it. On market day, we saw goat meat displayed in the open air, the severed heads in proud prominence to demonstrate freshness. One can even go to the slaughter area to see the entire process. For a Western mind, this may seem gruesome. Yet it is the truth for each animal whose body parts we see so neatly dissected, packed into Styrofoam and cling-wrapped at the grocery store. In Happy Valley, you get the whole story.

Excerpted with permission of the author and Rocky Mountain Books from Jane Marshall’s Searching for Happy Valley copyright 2023, Rocky Mountain Books.